What we heard report: Revisions to the Code of Conduct for Procurement

On this page

- I. Background

- II. Overview of consultation

- III. Limitations of methodology

- IV. Questionnaire feedback

- V. Survey feedback from Public Services and Procurement Canada vendors

- VI. Conclusions

- Annex 1: Code of Conduct—Questionnaire

- Annex 2: Code of Conduct—Questionnaire

I. Background

Millions of people are in situations of forced labour worldwide in a broad range of industries. Risk factors such as weak government oversight of labour laws, absence of a free press, and institutionalized corruption can create environments that foster and perpetuate forced labour and other forms of labour exploitation.

Forced labour is deeply embedded in the complex structure of the modern global economy and is usually found in the bottom tiers of the supply chainFootnote 1 where raw materials are first collected and processed. Governments, companies and consumers are often unaware that the products they have acquired may have been produced through exposure to exploitative practices.

To combat these types of abuses, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) was developed in 2011 with the aim of establishing an international standard that articulates the responsibilities that governments and the private sector share in ensuring that human rights are universally respected. This includes, but is not limited to, safeguarding workers’ human and labour rights, particularly regarding risks of forced labour in businesses’ main operations and supply chains.

On September 4, 2019, the Government of Canada launched the National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking 2019 to 2024, which includes a commitment for Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) to update the Code of Conduct for Procurement (the code) to outline human rights expectations, and to develop and implement tools to support vendors in meeting these expectations. The code was first announced as a key milestone in the implementation of the 2006 Federal Accountability Act to reform federal procurement. The first version of the code was posted in September 2007 and has since undergone 2 subsequent revisions in September 2012 and November 2014.

The inclusion of human and labour rights expectations into the code is a key step in a multipronged approach to address human trafficking in government procurement supply chains.

II. Overview of consultation

From January 13 to February 19, 2021, PSPC engaged in a consultation process seeking input from the vendor community, non-governmental organizations, experts, and other government departments to share their views on proposed updates to the code.

“I would like the Canadian government to lead the way in codes of conduct for Canadians doing business—and set an international standard for integrity and dignity in business and government.

Thank you for this document.”

The objectives of the consultation process were to:

- seek input on proposed changes to the code, particularly regarding new content outlining human and labour rights expectations

- enhance awareness of vendors of forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains

- identify tools, resources, and initiatives to support vendors in meeting expectations of the revised code

As part of the consultation process, the following supporting documents were posted on the Buyandsell.gc.ca website:

- the proposed draft code

- questions and answers document

- questionnaire for feedback on the proposed draft code (Annex 1)

- survey for PSPC vendors with a human and labour rights focus (Annex 2)

III. Limitations of methodology

The findings presented in this report are based on 237 responses: 64 from the questionnaire for feedback on the proposed code, and 137 from the survey for PSPC vendorsFootnote 2. Given these numbers, findings and conclusions should not be considered statistically representative of the opinions of our vendors. Although the findings suggest several potential key themes and challenges, broader research, consultation, and data analysis would be required to verify these conclusions.

IV. Questionnaire feedback

Questionnaire respondents included non-governmental organizations, experts, academia, and other government departments.

Overall, the majority of questionnaire respondents noted that the content of the proposed draft code was clearly articulated, thorough, and reflected Canadian values. In addition, the new human and labour rights content was well-received.

“I believe that any company that does work for the Government of Canada should adhere to a high standard of conduct as it is a reflection on Canada itself and what it stands for.

I believe all companies should follow these standards and I applaud this effort.”

Concerns focused primarily on the following themes:

- compliance monitoring

- supply chain monitoring

These are discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

Compliance monitoring

Respondents raised general concerns about how compliance with the code would be monitored, particularly in cases where a breach of the code is detected in a vendor’s main operations or supply chain.

“Moving forward, we believe it will be essential to clarify–and if necessary, establish–processes for monitoring adherence to the code and receiving inquiries and complaints from stakeholders related to non-compliance.”

Given the global context in which many companies operate, respondents were also concerned about the challenges involved in monitoring compliance with local laws and international human and labour rights in other countries. A small number of vendors also speculated about the potential costs that may be incurred through compliance monitoring activities.

The absence of compliance mechanisms to enforce the code was also noted, and presents an opportunity for further development.

1 respondent noted that if the code was to have meaningful impact, a horizontal policy approach that included procurement reform and supply chain legislation would be needed.

Supply chain monitoring

Respondents expressed concerns about how to monitor their supply chains in order to be compliant with expectations set forth in the code. Becoming aware of activities within complex, global supply chains was identified as a challenge, particularly as clandestine crimes such as human trafficking, forced labour, and other human rights violations are actively concealed.

“I am not aware of the way of working of all the organizations involved in the transformation and creation of a product.”

Vendors involved in the creation of goods such as electronics, with highly complex and dispersed global supply chains with many tiers of sub-contractors, noted the logistical and administrative challenges that may be involved with ensuring that their supply chains are compliant with the code.

“We would recommend a more direct approach on tackling recruitment fees as they are a strong indicator of forced labour and human trafficking.”

As a potential response, some vendors noted that measures could be taken to discourage practices connected with human rights violations.

Challenges on how (or if) to engage in the procurement of goods from countries with known or suspected ties to widespread human rights abuses was raised by several respondents. Some vendors also suggested incentivizing the increased procurement of domestically produced goods with either Canadian or North American supply chains.

These concerns underscore the need for the Government of Canada to make available and, where applicable, to develop awareness-building tools and resources to enable vendors to better understand and mitigate the potential risks of human rights violations that may be present within their supply chains.

V. Survey feedback from Public Services and Procurement Canada vendors

In addition to seeking input on proposed updates to the code, this consultation sought feedback from vendors through a survey in order to understand their current level of awareness and preparedness to mitigate risks in their supply chains related to forced labour and human trafficking.

Feedback by category is summarized below.

Corporate social responsibility

The Government is Canada has been a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) since December 14, 1960, and is committed to advancing key corporate social responsibility (CSR)Footnote 3 priorities, notably through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, which sets out expectations from governments to businesses on critical areas, including human and labour rights.

Given the ongoing importance of CSR, and the enhanced human and labour rights expectations proposed in the updated code, the survey sought to determine the extent to which existing CSR policies were in place amongst the vendor community.

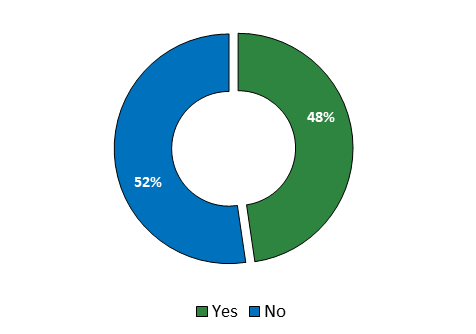

Of the survey respondents, 48% indicated that they have a CSR policy in place.

Table 1: Percentage of respondents with a corporate social responsibility policy

Image description

Percentage of respondents with a CSR policy

48% of respondents indicated yes, they have a CSR policy in place.

52% of respondents indicated no, they do not have a CSR policy in place.

Supply chain mapping

The updated code includes expectations that vendors and their Canadian and foreign vendors guarantee employees’ fundamental human and labour rights, as elaborated under the International Labour Organization’s 8 fundamental conventions and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

These expectations apply to vendors’ main operations as well as those of any sub-contractors within their supply chains. Under the code, vendors are expected to take steps to monitor their supply chains to ensure that they are free from exposure to human rights violations.

To this end, the survey sought to determine the level of supply chain awareness of vendors.

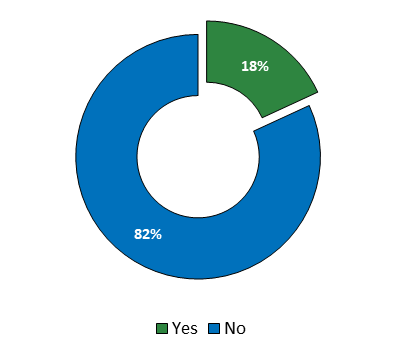

Of the survey respondents, 18% indicated that they have fully mapped out their supply chains.

Those who reported mapping their supply chains indicated using Microsoft’s Dynamics 365 Supply Chain Management, Excel spreadsheets, Google Workspace, or a mix of in-house and proprietary software solutions.

Table 2: Percentage of respondents who have mapped their supply chains

Image description

Percentage of respondents who have mapped their supply chains

18% of respondents indicated yes, they have mapped their supply chains.

82% of respondents indicated no, they have not mapped their supply chains.

Forced labour measures

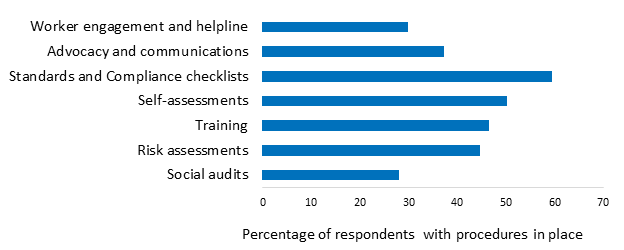

Of the survey respondents, 32% indicated that they had measures in place to address risks of forced labour, child labour or human trafficking in their global supply chains.

Of the 32% of respondents with forced labour measures in place, the most used options were compliance checklists, self-assessments, and training resources (see Table 3.1 below)

Table 3: Percentage of respondents with forced labour prevention measures

Image description

Percentage of respondents with forced labour prevention measures

32% of respondents indicated yes, their organization has forced labour prevention measures in place.

68% of respondents indicated no, their organization does not have forced labour prevention measures in place.

Table 3.1: Forced labour prevention measures

Image description

| Prevention measure | Percentage of respondents with procedures in place |

|---|---|

| Worker engagement and helpline | 29.6 |

| Advocacy and communications | 37.0 |

| Standards and compliance checklists | 59.3 |

| Self-assessments | 50.0 |

| Training | 46.3 |

| Risk assessments | 44.4 |

| Social audits | 27.8 |

International human rights reporting requirements

The majority of respondents indicated they are not subject to international due diligence reporting requirements on forced labour, human trafficking, modern anti-slavery, or human rights.

Of the 8% of survey respondents that noted being subject to international reporting requirements, the majority were subject to the United States Federal Acquisition Regulation Combatting Trafficking in Persons Requirements (2015) and the United Kingdom Modern Slavery Act (2015).

The US legislation applies to all federal contracts and subcontracts and includes compliance plan requirements for any portion of contracts with estimated values in excess of $500,000 for supplies acquired outside of the United States. These plans require vendors to outline actions taken to mitigation the risks of human trafficking and other human rights violations.

Under the UK legislation, the businesses with annual incomes in excess of £36 million (approximately $63.2 million CAD) are required to publish annual statements guaranteeing that steps have been taken to identify instances of slavery and human trafficking in their supply chains.

Departmental actions to mitigate risks of forced labour

When asked what PSPC could do to address the risks of forced labour in federal supply chains, respondents ranked the following as the 3 most preferred options:

- banning vendors that are in non-compliance with human and labour rights requirements in other jurisdictions

- create publicly available lists of vendors and sub-contractors that are found to be in non-compliance with human and labour rights in their supply chains

- require vendors to self-certify that they take steps to eliminate forced labour from their supply chains

The remainder of options, ranked in order of preference were: creation of special contract termination clauses, creating incentives for vendors to conduct human and labour rights due diligence, and establishing compliance monitoring systems.

Potential initiatives to support vendors

When asked what PSPC could do to support vendors to address the risks of forced labour in their operations and supply chains, respondents ranked the following as the 3 most preferred options:

- develop information resources for vendors and workers in the supply chain

- develop standards and compliance checklists

- develop training for vendors

The remainder of options, ranked in order of preference were: rewarding socially responsible behaviours in the procurement process, and requiring vendors to report their efforts to address forced labour in their supply chains.

VI. Conclusions

The majority of respondents to the questionnaire are supportive of updates to the code to include human and labour rights requirements. Many vendors already have CSR policies in place and are committed to expanding their responsible business practices. To that end, many respondents signaled that PSPC could take supplementary measures to ban vendors that are in non-compliance with human and labour rights expectations.

The following themes emerged as strategic opportunity areas for PSPC to have greater impact in supporting the vendor community to mitigate and address forced labour, and to meet the new human and labour rights expectations within the Code of Conduct.

Increasing awareness

Increasing awareness, particularly with respect to complex, global supply chains, remains an ongoing challenge. The results of this consultation suggest that the majority of PSPC vendors have not mapped their supply chains and are unaware of risks related to forced labour and human trafficking.

Facilitating supply chain analysis tools

The consultation revealed the need to provide vendors with access to the tools and resources that will enable them to comply with supply chain expectations within the code, and in so doing, to mitigate potential risks of human rights violations within their supply chains.

Tracking progress

In order to track changes in vendors’ levels of awareness and to identify trends in mitigation strategies, there will be a need for periodic surveying.

PSPC will continue to engage with the vendor community to ensure that the code is, and continues to be, a clear statement of values and expectations that safeguards federal procurement supply chains, and guides the ethical procurement of goods on behalf of Canadians.

Annex 1: Code of Conduct—Questionnaire

Please see below the 5 questions seeking feedback on proposed updates the code.

Question 1

Are you responding as a/an:

- vendor

- academic

- non-government organization

- other, please specify

Question 2

Is the draft Code of Conduct clear?

Question 3

Is there anything in the draft Code of Conduct that you consider challenging for your organization? If yes, please identify.

Question 4

Is there anything related to human trafficking or forced labour that you would like to see included or revised in the draft Code of Conduct?

Question 5

Do you have any other comments about the Code of Conduct in general?

Annex 2: Code of Conduct—Survey

Please see below the 7 survey questions designed to understand the current level of awareness and preparedness of the vendor community to mitigate risks in their supply chains related to forced labour and human trafficking.

Question 1

Does your organization possess a corporate social responsibility policy or Code of Conduct? (yes/no)

Question 2

Has your organization mapped its supply chains? (yes/no)

Question 3

Does your organization have any procedures in place to address forced labour, child labour or human trafficking in its global supply chains? If Yes, please select the ones that apply:

- social audits

- risk assessments

- training

- self-assessments

- standards and compliance checklists

- advocacy and communications

- worker engagement and helpline

- other, please specify

Question 4

Is your organization subject to international reporting requirements requiring you to report on actions taken to minimize risks of forced labour in your supply chains? If Yes, please select the legislative requirements that apply:

- UK Modern Slavery Act (2015)

- UK Modern Slavery Act (2015) is a British legislation that requires companies with a global revenue of at least £36 million providing goods or services in the UK, to report on the steps the company has taken to ensure modern slavery is not occurring in its supply chains

- Australia Modern Slavery Act (2018)

- Australia Modern Slavery Act (2018) is a legislation that requires all companies operating in Australia with revenues of at least AU$100 million, to submit a report to a publicly-available register, identifying the potential modern slavery risks in a company’s supply chains and the actions taken to address them

- California Transparency in Supply Chains Act (2010)

- California Transparency in Supply Chains Act (2010) is a legislation that requires manufacturing and retail businesses in California with an annual worldwide revenue of at least US$100 million, to publicly report on whether their supply chains have been audited to address the risks of human trafficking and slavery

- United States Federal Acquisition Regulation Combatting Trafficking in Persons Requirements (2015)

- United States Federal Acquisition Regulation Combatting Trafficking in Persons Requirements (2015) requires a compliance plan and certification requirements for procurements in excess of US$500,000 for goods and services acquired outside the US and prohibits Federal contractors and subcontractors from engaging in human trafficking. Contractors in violation of the provisions can be suspended or debarred from conducting business with the US Government

- France Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law (2017)

- France Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law (2017) establishes an obligation for parent companies to prepare a due diligence plan that addresses impacts on the environment, and human rights (including modern slavery) for all French companies that have more than 5,000 employees domestically or employ 10,000 employees worldwide

- Germany CSR Directive Implementation Act (2016)

- Germany CSR Directive Implementation Act (2016) requires large companies of public interest for example, capital market-oriented companies, credit institutions, and insurance companies having an average number of employees in excess of 500 workers, to disclose information on environmental matters, social and employee-related matters, on respect for human rights and on anti-corruption and bribery matters

- wasn’t aware of any of these international reporting requirements

- other, please specify

Question 5

Is your organization certified by any of the following?

- ISO 26000

- ISO 26000 is an international standard developed to help organizations clarify what social responsibility is, and shares best practices relating to social responsibility, globally. It is intended as guidance, not for certification

- ISO 45001

- ISO 45001 is an international certification standard for occupational health and safety. It provides a framework to increase safety, reduce workplace risks and enhance health and well-being at work

- SA 8000

- SA 8000 is a certification standard that encourages organizations to develop, maintain, and apply socially acceptable practices in the workplace. It measures the performance of companies in 8 areas important to social accountability in the workplace: child labour, forced labour, health and safety, free association and collective bargaining, discrimination, disciplinary practices, working hours and compensation

- N/A

- Other, please specify

Question 6

What should PSPC do to address the risk of forced labour in suppliers’ supply chains? Please select the top 3:

- require suppliers to self-certify that they take steps to eliminate forced labour from their supply chains

- create special contract termination clauses

- establish a compliance monitoring system to assess vendors’ compliance with human and labour rights

- create a public list of vendors and sub-contractors that are found to be in non-compliance with human and labour rights in their supply chain

- ban vendors that are in non-compliance with human and labour rights requirements in other jurisdictions

- develop standards and compliance checklists

- create incentives in the procurement process to encourage vendors to conduct human and labour rights due diligence

- other, please specify

Question 7

How can PSPC help you to address risks of forced labour in your businesses operations and supply chains? Please select the top 3:

- develop information resources for suppliers and workers in the supply chain

- develop training for suppliers

- require suppliers to report on their efforts to address forced labour in their supply chains

- reward socially responsible behaviours in the procurement process

- develop standards and compliance checklists

- Date modified:

- 2021-10-28