Public Services and Procurement Canada

Evaluation of the Contract Security Program

On this page

Executive summary

i. Governments around the world routinely work with information and assets that, when not properly safeguarded, have the potential to have impacts on both national and international interests. In the most extreme cases, the compromise of highly classified information could represent substantial threats to national or global security. To mitigate these risks, governments have instituted mechanisms to ensure that sensitive information and assets are properly safeguarded when held internally within government. In addition, through the course of government contracting, it is also often necessary for businesses or other external organizations to access protected or classified information, assets and work sites. The Contract Security Program (CSP) exists to help ensure that these materials and sites are properly safeguarded and secured within the context of these contracts.

ii. This evaluation examined the relevance and performance of the CSP. The objective of this program is to help ensure that government information and assets are safeguarded during the contracting process. The program operated with a total budget of $22.1 million in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal yearFootnote 1 with 252 full time equivalents. Contract security functions have taken place in the Government of Canada since the 1940s.

iii. The program is located within the Departmental Oversight Branch of Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) in the Industrial Security Sector.

iv. Federal legislation and various policies outline key responsibilities of PSPC in administering an industrial security program. There continues to be a need for the CSP as the department has specific responsibilities for managing security in domestic and international government contracting. These responsibilities link the program to the departments' strategic outcome of ensuring sound stewardship in the context of security in government contracting. Ongoing requests for program services indicate a continuing and ongoing need for the program.

v. Overall the program is meeting the security requirements for domestic and foreign government contracts, and government information is safeguarded. Clients are generally satisfied with program services, but several were dissatisfied with the timeliness of classified security clearances. The program experienced increased volumes in the Personnel Security Screening Division which resulted in difficulties meeting their performance standards. Contractors working for the federal government generally understand their roles and responsibilities related to security in contracting. The Canadian government undertakes a high number of contracts with security requirements annually, with very few instances of information breaches. The program conducted a limited number of international investigations. There were 5 security breaches over the evaluation period, and all were deemed low risk by the program. The program supports secure international contracting, and provides services to foreign governments to help ensure that their information will be safeguarded while in the custody of Canadian contractors.

vi. The program experienced challenges in the delivery of timely and cost-effective personnel screenings. A number of initiatives are underway to further improve program delivery and client services. Limited information on program economy was available as a result of outcome attainment being influenced by a large number of factors outside of the programs scope.

Management response

vii. The Departmental Oversight Branch Contract Security Program is a key contributor to the national security framework, engaging closely with Security and Intelligence agencies and departments to identify, evaluate and mitigate security risk in government contracting. This includes the application of safeguards to all phases of the government contracting process as a lead security agency, allowing Canadian industry to participate in domestic and international government contracting while safeguarding sensitive government information and assets.

viii. Since the completion of data gathering for this evaluation in March, 2017, the CSP has seen significant, sustained performance improvement. Publicly reported service delivery standards for all screening levels have been met or exceeded over the past 4 quarters. In addition, processing timelines for security requirement check lists have improved such that the 15-day standard is met 80 to 90% of the time. These performance improvements have resulted from: transition to paperless processes, on-going workforce stabilization, re-engineering of security screening processes, and increased use of risk-based prioritization for complex files and investigations. In addition, pilot programs to address domestic visit requests (with the Department of National Defence) and regional security investigations are underway and are expected to further decrease processing times.

ix. Given that the steps taken over the last year have led to sustained performance improvement, Departmental Oversight Branch does not consider the development of a risk framework to be necessary in order to balance security and client service, with a view to improving process times. However, an ongoing threat and risk assessment will be used to apply a risk-based lens to the CSP, with a view to improved risk mitigation in an evolving threat environment. In addition, recent public opinion research conducted on the CSP has provided baseline data that will be used to evaluate progress related to improving industry's awareness of its security obligations in the government contracting process.

Recommendations and management action plan

Recommendation 1

The Assistant Deputy Minister, Departmental Oversight Branch should develop a risk framework to balance the 2 core objectives of security and client service with a view to improve processing times for classified personnel screening, visit requests and security requirements check lists. Furthermore, this framework should include an approach to foreign ownership, control or influence to mitigate the risk of unauthorized access to sensitive information as well as information technology security considerations in contracting.

Management action plan 1.1

In order to improve processing times for classified personnel screening, visit requests and security requirements check lists, the following has been undertaken:

- transition to paperless processes using E-signature

- implementation of telephone interviews for minor adverse and instances of non-disclosure

- re-engineering of internal security screening process resulting in significant improvements in processing times

- development and implementation of new risk-based matrixes for complex files to reduce the number of files requiring security screening interviews and investigations

- stabilized resources: reduced dependency on contingent workforce

- development and implementation of a pilot (through March 2020) to develop a regional security screening investigator capacity to improve performance in key regions

- development of a plan to pilot the processing of domestic visit requests by the Department of National Defence. Pilot to be launched by quarter 1 of the 2019 to 2020 fiscal year

Management action plan 1.2

As part of a more holistic assessment of the factors and risks that company ownership may represent to the security of information, the CSP will undertake a review of ownership processes, informed by the ongoing threat and risk assessment, and develop recommendations regarding risk-based review of ownership as part of the registration process.

Management action plan 1.3

PSPC will adopt a risk-based approach to addressing Information Technology (IT) inspection requirements to allow for the implementation of an offsite inspection process for low risk files to increase efficiency.

Recommendation 2

The Assistant Deputy Minister Departmental Oversight Branch should strengthen the program's performance measures related to its security objectives. This could include measures to ensure that company security officers are better aware of their role in reporting security breaches and events, and of the security measures required for subcontractors.

Management action plan 2.1

The Contract Security Program will take the following steps to strengthen program performance measures related to its security objectives, as they relate to industry awareness of contract security obligations:

- review and update communications material for industry regarding their contract security obligations related to breaches and subcontractors

- launch a new online training course for company security officers to raise awareness of the roles and responsibilities of contractors in complying with contract security requirements, including those related to breaches and subcontractors

- explore the feasibility of making online training mandatory, including a phased-in approach (for example, 1) pilot project; 2) mandatory in non-compliance cases; 3) mandatory for all)

- re-write the CSP's Industrial Security Manual to focus only on program requirements, and make it more user-friendly for industry

- review, assess and make recommendations on how to simplify clearances of subcontractors in the CSP

Introduction

1. This report presents the results of the evaluation of the Contract Security Program (CSP). This engagement was included in the Public Services and Procurement Canada PSPC 2017 to 2018 Risk-Based Audit and Evaluation Plan.

Profile

Background

2. Governments around the world routinely work with information and assets that, when not properly safeguarded, have the potential to impact both national and international interests. In the most extreme cases, the compromise of highly classified information could represent threats to national or global security. Governments also rely on private sector contractors to help deliver their mandates. To mitigate the risks related to safeguarding information and assets in the hands of contractors, governments have instituted mechanisms to help ensure that sensitive information and assets remain properly safeguarded. Canada's program, the CSP, only applies to businesses and individuals contracted by the government who require access to protected or classified information, assets and work sites.

3. To accomplish this goal, the CSP:

- screens businesses and individuals employed by those businesses that require access to sensitive information and assets as part of a contract with the federal government

- reviews all security requirements identified by contracting authorities before contracts are finalized

- develops standard security clause language for inclusion in federal contracts

- undertakes inspections and investigations to ensure contractors' organizations, facilities and employees are in compliance with industrial security requirements

- acts as a primary authority on contract security in Canada and abroad by participating in various domestic and international fora

- provides training and guidance to Canadian businesses on security issues

- develops policy instruments, guidelines, and tools related to security in contracting

- negotiates, administers and implements bilateral security instruments for the exchange of sensitive information with foreign countries and international organizations

4. Contract security has existed as a function within the Canadian government since the 1940s when the function was managed by the Department of Munitions and Supply. The 9/11 terrorist attacks influenced the security requirements placed on contractors and increased the demand for screening. In 2007, increased demand for international bilateral industrial security agreements and arrangements led to the creation of the International Industrial Security Directorate.

Authority

5. Section 6 of the Department of Public Works and Governments Services Act gives the Minister of Public Services and Procurement the authority to acquire and provide services to other government departments and to plan and organize the provision of materiel and services required by departments. As per the Treasury Board Policy on Government Security , federal departments are responsible for protecting sensitive information and assets under their control, and this requirement applies to all stages of the contracting process. The policy specifically identifies PSPC's responsibility as a lead security agency to provide leadership and coordination of activities to help ensure the application of security safeguards through all phases of the contracting process.

6. The Treasury Board Standard on Security Screening came into effect in October 2014 and outlines a common standard for personnel screening, which is applicable to both government employees and contractors requiring access to sensitive information, assets or sites. It outlines 2 responsibilities for the CSP: (1) conducting security screening of private sector individuals as part of the government contracting process, including those participating in foreign contracts; and (2) managing a visit clearance request system for visitors accessing classified information on private sector premises and for foreign private sector individuals accessing classified information on government premises.

7. The Treasury Board Contracting Policy requires contracting authorities to observe the provisions of its Policy on Government Security . It also recommends that user departments either seek guidance from or contract directly through a common service organization such as PSPC for contracts involving security requirements.

8. The Treasury Board Security and Contracting Management Standard requires contracting authorities to process their contracts through PSPC for contracts that afford access to sensitive foreign government information and assets (that is, contracts that allow foreign contractors access to sensitive Canadian government information and assets, and contracts that afford Canadian contractors access to sensitive foreign government information and assets).

9. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization Security Policy requires all North Atlantic Treaty Organization member countries to implement a contract security program in order to communicate to industry the national policy in all matters of North Atlantic Treaty Organization industrial security policy and providing direction and assistance in its implementation. PSPC was identified to fulfill this role.

Roles and responsibilities

10. The CSP functions are located in the Industrial Security Sector within the Departmental Oversight Branch. The CSP has both a domestic and an international component. The Canadian Industrial Security Directorate is responsible for conducting company and personnel screening, registration, inspections, investigations, and supplying valid security clauses for inclusion in contracts, among other activities related to domestic industrial security. The International Industrial Security Directorate negotiates international bilateral security instruments and conducts other international security roles related to security in contracting. Delivery of the program takes place in the National Capital Area.

Resources

11. The CSP's actual expenditures were $23.3 million in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. The program operates on a mix of cost-recovery and A-base funding. A-base was $6.3 million and $17 million was generated through cost-recovery in that same fiscal year. There were 252 full-time equivalent employees.

Logic model

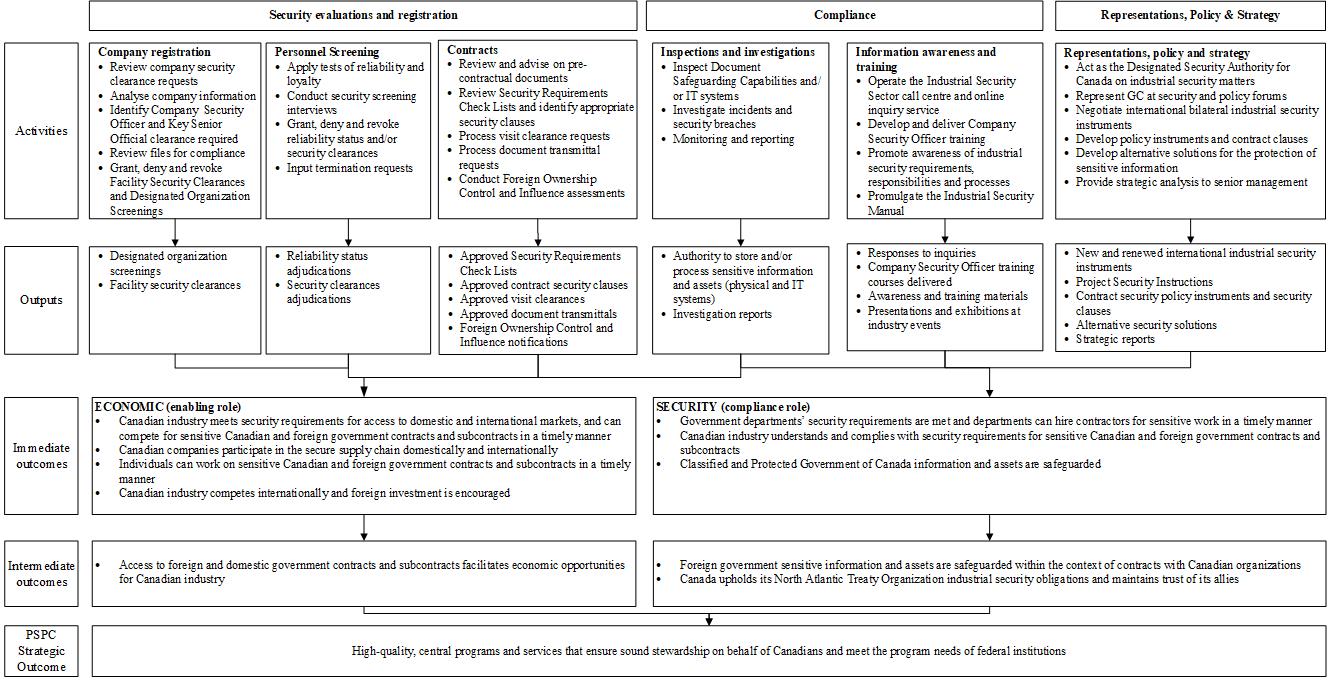

12. A logic model is a visual representation that links a program's activities, outputs and outcomes; provides a systematic and visual method of illustrating the program theory; and shows the logic of how a program is expected to achieve its objectives. It also provides the basis for developing the performance measurement and evaluation strategies, including the evaluation matrix.

13. A logic model for the program was developed based on a document review and was subsequently validated with program staff. The logic model is provided in Exhibit 1. A detailed summary of program activities can be found in Appendix A: Description of program activities.

Exhibit 1—Logic model for the Contract Security Program

Text version

This exhibit depicts the logic model of the evaluation of the Contract Security Program. The logic model depicts program activities, outputs, immediate outcomes, intermediate outcomes, and a Public Services and Procurement Canada strategic outcome.

Activities

The Contract Security Program includes 3 areas of activity:

The security evaluations and registration, compliance, and representations, policy and strategy activities are comprised of more detailed program activities.

Security evaluations and registration

The security evaluations and registration area of activity is comprised of 3 more detailed areas of activities:

Company registration:

- Review company security clearance requests

- Analyse company information

- Identify company security officer and key senior official clearance required

- Review files for compliance

- Grant, deny and revoke facility security clearances and designated organization screenings

Personnel screening:

- Apply tests of reliability and loyalty

- Conduct security screening interviews

- Grant, deny and revoke reliability status and/or security clearances

- Input termination requests

Contracts:

- Review and advise on pre-contractual documents

- Review security requirements checklists (SRCL) and identify appropriate security clauses

- Process visit clearance requests

- Process document transmittal requests

- Conduct foreign ownership control and influence (FOCI) assessments

Compliance

The compliance area of activity is comprised of 2 more detailed areas of activity:

Inspections and investigations:

- Inspect document safeguarding capabilities and/or information technology (IT) systems

- Investigate incidents and security breaches

- Monitoring and reporting

Information awareness and training:

- Operate the Industrial Security Sector call centre and online inquiry service

- Develop and deliver company security officer training

- Promote awareness of industrial security requirements, responsibilities and processes

- Promulgate the Industrial Security Manual

Representations, policy, and strategy

The representations, policy and strategy area of activity is comprised of 1 more detailed area of activity: Representations, policy and strategy.

The representations, policy and strategy area of activity is comprised of 6 activities:

- Act as the designated security authority for Canada on industrial security matters

- Represent Government of Canada at security and policy forums

- Negotiate international bilateral industrial security instruments

- Develop policy instruments and contract clauses

- Develop alternative solutions for the protection of sensitive information

- Provide strategic analysis to senior management

Outputs

The activity, company registration, leads to the following 2 outputs:

- Designated organization screenings

- Facility security clearances

The activity, personnel screening, leads to the following 2 outputs:

- Reliability status adjudications

- Security clearances adjudications

The activity, contracts, leads to the following 5 outputs:

- Approved security requirements check lists (SRCL)

- Approved contract security clauses

- Approved visit clearances

- Approved document transmittals

- Foreign ownership control and influence assessments (FOCI) notifications

The activity, inspections and investigations, leads to the following 2 outputs:

- Authority to store and/or process sensitive information and assets (physical and IT systems)

- Investigation reports

The activity, information awareness and training, leads to the following 4 outputs:

- Responses to inquiries

- Company security officer training courses delivered

- Awareness and training materials

- Presentations and exhibitions at industry events

The activity, representations, policy, and strategy, leads to the following 5 outputs:

- New and renewed international industrial security instruments

- Project security instructions

- Contract security policy instruments and security clauses

- Alternative security solutions

- Strategic reports

Immediate outcomes

The Contract Security Program includes 2 groups of immediate outcomes:

- Economic (enabling role)

- Security (compliance role)

The economic (enabling role) group of outcomes includes 4 immediate outcomes:

- Canadian industry meets security requirements for access to domestic and international markets, and can compete for sensitive Canadian and foreign government contracts and subcontracts in a timely manner

- Canadian companies participate in the secure supply chain domestically and internationally

- individuals can work on sensitive Canadian and foreign government contracts and subcontracts in a timely manner

- Canadian industry competes internationally and foreign investment is encouraged

The security (compliance role) group of outcomes includes 3 immediate outcomes:

- Government departments' security requirements are met and departments can hire contractors for sensitive work in a timely manner

- Canadian industry understands and complies with security requirements for sensitive Canadian and foreign government contracts and subcontracts

- Classified and Protected Government of Canada information and assets are safeguarded

Intermediate outcomes

The 4 immediate outcomes under the economic (enabling role) group of outcomes contribute to the following intermediate outcome: Access to foreign and domestic government contracts and subcontracts facilitates economic opportunities for Canadian industry.

The 3 immediate outcomes under the security (compliance role) group of outcomes contribute to the following 2 intermediate outcomes:

- Foreign government sensitive information and assets are safeguarded within the context of contracts with Canadian organizations

- Canada upholds its North American Treaty Organization (NATO) industrial security obligations and maintains trust of its allies

Public Services and Procurement Canada strategic outcome

The intermediate outcomes contribute to the PSPC strategic outcome: High-quality, central programs and services that ensure sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians and meet the program needs of federal institutions.

Focus of the evaluation

14. The objective of this evaluation was to determine the program's relevance and performance in achieving its expected outcomes in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results. The evaluation assessed the program for the period from April 1, 2011, to March 31, 2017.

Approach and methodology

15. An evaluation matrix, including evaluation issues, questions, indicators and data sources, was developed during the planning phase.

16. Multiple lines of evidence were used to assess the program. These included:

- Document review: Documents included legislative and policy documents; agreements; departmental documents (for example, annual reports on plans and priorities, departmental performance reports); and program documents such as annual reports and studies

- Literature review of similar jurisdictions: Only 1 jurisdiction (United States of America) that had a similar program was identified. The substantial differences in scope, scale, and structure limited the comparability of the programs

- Financial analysis: Financial data related to the program's budgets, revenues, and expenditures was examined to assess the economy and efficiency of the program. A basic analysis of the cost-per-output and cost relative to the timeliness of the outputs was also conducted

- Interviews: Nineteen interviews were conducted with key program staff and stakeholders, including 7 with program staff, 4 with client departments, 5 with industry, and 3 with other federal stakeholders

- Surveys: Two surveys of industry stakeholders were conducted. The survey of key senior officials was sent to 523 individuals and there were 152 valid responses, for a response rate of 29%. The survey of company security officers was sent to 575 individuals and there was 125 valid responses, for a response rate of 22%

17. More information on the approach and methodologies used to conduct this evaluation can be found in Appendix B: About the evaluation section.

Findings and conclusions

18. Two themes emerged during the course of the evaluation that highlighted a unique balance that the CSP strives to maintain while delivering on its mandate: stewardship in government security and the client-centred delivery of services. Information gathered as part of the evaluation indicate that the rationale and relevance of the program centres on the stewardship role held by the program – ensuring and maintaining security as part of government contracts. This was identified as not only a priority for the organization, but also as a main responsibility. Delivering on this role however poses a unique challenge as the program strives to protect government information and assets, as well as deliver its services in a streamlined, efficient, and client centered manner.

19. The performance aspect of the program examined as part of the program's ongoing performance measurement and the evaluation indicate that the assessment of the program's performance is tied to its role in delivering timely services to clients. The ultimate outcome of the program points to security, yet the program's performance is primarily linked with its ability to deliver timely services to clients. As a result, a focus on performance measures identified by the program will not provide a fulsome performance story, in particular in relation to its success in safeguarding assets. Further, because there is a potential for conflict between timeliness (an economic impact measure) and rigour (a security impact measure), there is a risk that the measures will drive program activities that would negatively impact its stewardship role. The evidence provided below features an analysis of both the program's role in stewardship and in the delivery of client-centered services.

Relevance

Continued need

Does the program address a demonstrable need and is it responsive to the needs of the federal government and Canadian industry?

Conclusion

20. There are factors present which are similar to the original rationale of the program and demand for program outputs is steady. There are legislative and policy requirements for the CSP. There continues to be a demonstrable need for the program and stakeholders were generally in agreement that the CSP fulfills a continuing need.

Findings

Continued existence of factors that were at the basis of the original rationale for the program.

21. The Industrial Security Branch was established under the former Department of Munitions and Supply in 1941. The original rationale for the creation of the branch was to help ensure that "the contractors of Canadian plants engaged in war supplies met the security requirements of their contract relating to the protection of their plants against espionage and sabotage".

22. The program's current operations have a similar goal of helping ensure that government materials and assets are properly safeguarded and secured within the context of government contracts, both domestically and internationally. The Canadian government relies on contracts for various goods and services, often with security requirements.

23. Stakeholders were generally in agreement that the CSP fulfills a continuing need. They noted that since government information and assets are being entrusted to the private sector, these need to be protected and safeguarded as per the contract. Stakeholders also felt that the CSP enabled their organization to meet the security requirements necessary to be awarded Canadian government contracts and subcontracts, and to compete and participate in contracts with foreign governments.

Demand for the program measured in volume and trend of transactions.

24. Demand for the industrial security services has grown dramatically since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States. The main drivers for the increased demand are the: security requirements for those requiring access to government buildings and information; number and size of international cooperative projects that require security clearances; and, the number of Canadian government contracts, both military and non-military. The highest volume of CSP transactions are personnel security screenings, visitor and document requests and security-related contract clauses for inclusion in government contracts.

Legislative/regulatory/policy requirements for the program.

25. Section 6 of the Public Works and Government Services Act gives the Minister of Public Services and Procurement the authority to acquire and provide services to other government departments. The CSP's goal is to ensure that government materials and sites are properly safeguarded and secured within the context of government contracts.

26. The Security of Information Act identifies the various offences and the penalties that pertain to the mishandling of classified information or the communication of classified information to an unauthorized person. This further demonstrates the need for the program. The CSP provides this type of assurance, while at the same time supporting government operations and facilitating work that supports the Canadian economy.

27. The Treasury Board Security and Contracting Management Standard states that for contracts that fall outside of "a department's delegated contracting responsibilities and that involve access to sensitive information and assets, PSPC is responsible for ensuring compliance with the appropriate security requirements".

28. It is also responsible for ensuring compliance with international security instruments. Furthermore, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization Security Policy requires all North Atlantic Treaty Organization member countries to implement a contract security program, which PSPC fulfills for the government of Canada.

Federal priorities and departmental strategic outcomes

Does the program align with the priorities of the federal government? Does the program align with the priorities and strategic outcomes of PSPC?

Conclusion

29. The evaluation found evidence of direct program alignment with government priorities, and the program is aligned with PSPC priorities and the strategic outcome for the department.

Findings

30. The December 2015 Speech from the Throne indicated that the "Government is committed to providing greater security and opportunity for Canadians". The mandate letter to the Minister of PSP however, does not make mention of any explicit priorities related to security or the protection of government information in contracting. The program does however support the government's stated priority of growing the economy through ensuring security in government contracting.

31. CSP objectives align with the priority area identified in the 2017 to 2018 fiscal year PSPC Departmental Plan of providing "the government of Canada with high quality, timely and accessible specialized services and programs in support of sound, prudent and ethical management and operations". The program seeks to meet the need of its clients while at the same time protecting government information and assets while in the custody of industry.

32. The CSP is aligned with the strategic outcome of the department to "deliver high-quality, central programs and services that ensure sound stewardship on behalf of Canadians and meets the program needs of federal institutions". The CSP aims to ensure sound stewardship in its responsibilities related to security in government contracting.

Appropriate role and responsibility for the federal government

Does the program align with federal and PSPC roles and responsibilities?

Conclusion

33. The program is aligned with the roles and responsibilities of PSPC and the federal government in ensuring that government information and assets are protected while in the custody of contractors. The program performs functions for other government departments that those departments are authorized to perform themselves, when contracting under their delegation. Above their delegated spending authority, departments are to use the CSP. The program provides key functions in international contracting, and departments must engage the CSP when administering foreign contracts.

Findings

Evidence of the federal governments' roles and responsibility in relation to the delivery of the program.

34. As per the Policy on Government Security (6.1.6), deputy heads are responsible for "ensuring that all individuals who will have access to government information and assets … are security screened at the appropriate level before the commencement of their duties."

35. The Public Works and Government Services Act provides the Minister of PSP with the authority to acquire and provide services to other government departments and to plan and organize the provision of materials and services required by departments. Responsibility for screening and ensuring that persons working under contract for the federal government is the responsibility of the organization initiating the contract. As such, PSPC is responsible for providing the framework for the safeguarding of information and assets as part of its departmental contracts and for all Government of Canada contracts with foreign suppliers and when contracts require access to North Atlantic Treaty Organization and foreign classified information and assets. The Security and Contracting Management Standard states that departments must engage CSP for contracts that are above the delegated authority and should consider using the services of PSPC when the security requirements are complex and require more than personnel screening.

36. The Treasury Board Policy on Government Security identifies PSPC as the Lead Security Agency to provide leadership and coordinate activities to help ensure the application of security safeguards through all phases of the contracting process.

37. Program management and clients noted that PSPC with its client centered focus and its important role in government procurement makes it a good fit for an industrial security program.

Extent to which the program complements, duplicates or overlaps with other federal government functions, or with those of other levels of government, or the private sector.

38. The program conducted a duplication analysis for fiscal years 2015 to 2016 and 2016 to 2017 to determine the extent of duplication between the contractor security screenings and the number of screenings conducted by other federal organizations. The analysis concluded that PSPC completed 89% of the screenings for individuals employed by contractors at the reliability, secret and top secret levels. PSPC estimates that 1 in 5 security screenings performed for contractors of the federal government are conducted by both PSPC and another department. Because Canada has a decentralized model for its handling of sensitive information and assets, each departments can undertake their own screening of contractors (under their delegated spending authority).

39. Client departments noted that government departments do similar personnel screening work for their employees upon hiring, and that this same screening work could be undertaken for individuals employed by contractors. Providing contractor facility clearances for Government of Canada contracts however, is the responsibility of the CSP. Another client group noted that there is often a substantial amount of duplication in screening contractor personnel when a contract is managed by PSPC on behalf of a security or intelligence organization. Both organizations complete security checks, although the check conducted by the security or intelligence organization is often more extensive.

Conclusion: Relevance

40. Federal legislation and various policies outline key responsibilities of PSPC in administering an industrial security program. There continues to be a need for the CSP as the department has specific responsibilities for managing security in domestic and international government contracting. These responsibilities link the program to the department's strategic outcome of ensuring sound stewardship in the context of security in government contracting. Ongoing requests for program services indicate a continuing and ongoing need for the program.

Performance

Immediate outcome achievement

Outcome 1

To what extent does Canadian industry meet security requirements for access to domestic and international markets? To what extent can Canadian industry compete for sensitive Canadian and foreign government contracts and subcontracts in a timely manner?

Conclusion

41. The number of organizations that meet the security requirements for government contracts increased over the last 6 years as registration and screening volumes increased over the same period. Generally, the CSP experienced mixed results in delivering its services against its service standards associated with timeliness for classified security screenings. The program did however make significant improvements in reducing screening times for designated organization screenings and facility security clearances. The program opened new markets to Canadian industry by increasing the number of signed international bilateral security instruments. Although a smaller number of international contracts compared to domestic contracts with security requirements were issued over the evaluation period, the international component of the CSP grew, delivering support to international procurement activities. Industry representatives surveyed had limited awareness of the CSP's bilateral security instruments.

Findings

Domestic Industrial Security

42. In the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year, there were 11,807 organizations registered in the CSP, and this number increased to 20,808 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year.

43. Comparing the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, the volumes of screening requests receivedFootnote 2 increased from 67,650 (reliability status) and 36,542 (non-reliability status) to 94,994 and 45,139 respectively. The total number of requests completed annually also increased from 100,390 in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 139,774 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, and since the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year between 31% and 37% of all files completed are for classified clearances. The program denied 89 applications for security screening over the evaluation period.

44. The program undertakes a variety of other operations. Descriptions of the activities can be found in Appendix A: Description of program activities. The following trends were observed.

Industrial security operations: overall the processing times for designated organizational screening decreased from 112 average processing days in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 50 days in fiscal year 2016 to 2017. The average processing times for secret level facility security clearances decreased from the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year from 258 days in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 139 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. The average processing time for document safeguarding capabilities protected B decreased from 196 days in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 106 days in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, and secret also decreased during this same time period, from 256 days to 233 days.

Contracts: the program saw a decrease in its ability to deliver security requirements check lists within the 15 day service standard between April 2011 and March 2017, from 81% to 46%. This was contrasted with an improvement in the processing time for electronic security requirements check lists within the 2 day service standard from 87% in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 90% in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. The program mainly processes clauses for domestic contracts, but also processes clauses for international contracts.

Visits: overall the program saw the turnaround times decrease for visitor requests between the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year and the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year with requests being granted within the 15 day service standard 69% of the time in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 52% in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year.

Industrial security call centre: the program experienced variance in its ability to respond or refer incoming calls to the call centre. Since fiscal year 2011 to 2012, the percentage of calls to the call centre which were responded to or referred within 2 business days declined from 96% to 87% in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. The number of inquiries to the CSP increased between the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year and the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year from 58,241 in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 89,639 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year.

45. Program management indicated that there have only been a few cases that they are aware of where companies have lost opportunities due to security requirements not being met for a contract. In cases where the CSP is responsible for a delay, the program has in the past provided a quicker, lower level security clearance to a contractor so that they may begin work on less sensitive work before the final clearance is granted to prevent a company from losing a contract. As well, the CSP is working with the Acquisitions Branch of PSPC to identify the optimal time in the contracting lifecycle for when security requirements need to be met (for example, at the time of bidding or at contract award). This will help reduce screening volumes.

International Industrial Security

46. The Government of Canada works with foreign governments to safeguard the exchange of protected and classified information, and to help Canadian organizations compete internationally. To this end, Canada has negotiated bilateral industrial security instruments with various countries.

47. As of December 2017, there were 19 international bilateral security instruments in place between Canada and foreign nations. Seven were formalized between April 2011 to March 2017, 9 finalized between 1964 and early 2011. Six others were renewed between 2012 and 2017, for a total of 19. There is no established timeframe for the renewal of bilateral security instruments but recently clauses were added stipulating that they must be reviewed every 2 years to determine if there are any required changes.

48. The CSP implements a number of different international security processes to protect government information. These tools serve as alternatives to bilateral security agreements (used in countries that may not be covered by a bilateral security instrument) or can cover any gaps that may exist in an established security agreement. Project security, international contract clauses and alternative security solutions serve this purpose.

49. Project security instructions are security requirements that may fall outside of internationally recognized standards and bilateral industrial security instruments. There were 6 project security instructions developed by CSP over the evaluation period.

50. Alternative security solutions use security clauses to ensure that foreign contractors and subcontractors safeguard Canadian protected information according to similar standards as Canadian suppliers. The framework outlines the proper handling and safeguarding of Protected A and B information and assets abroad. There was a steady increase in the number of contracts using alternative security solutions between the 2013 to 2014 fiscal year (50) and the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year (689).

51. The number of international clauses in contracts which the program started tracking in late 2014 to 2015 fiscal year, shows that over the last 2 fiscal years, the numbers increased from approximately 1,050 in the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year to 10,355 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. While we are not able to identify a trend based on only 2 years of data, the numbers indicate that there was a dramatic increase in the number of international clauses developed by the program. The increase resulted from a Department of National Defence contracting requirement necessitating security requirements check lists for all international contracts.

52. Program data indicates that there were 689 international contracts with security requirements in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. Of the company security officers surveyed, 40% were aware of the instruments, and of the key senior officials surveyed, 51% were aware. This is likely related to these companies having little experience with international contracts.

Outcome 2

To what extent do Canadian companies participate in the secure supply chain domestically and internationally?

Conclusion

53. There were over 6,500 Canadian companies awarded contracts and participated in the secure supply chain domestically between fiscal years 2011 to 2012 and 2016 to 2017. Canadian companies were also afforded the opportunity to participate in the secure supply chain internationally through their registration in the CSP.

Findings

54. There were 6,561 Canadian suppliers awarded contracts with security requirements between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2017. It was not possible to outline a trend due to data limitations. Similarly it was not possible to distinguish between the suppliers who provided goods versus services.

55. As an indication of magnitude of contract awards, between fiscal years 2011 to 2012 and 2016 to 2017, over $36 billion worth of contracts with security requirements were registered in PSPC's Acquisitions Branch contracting database.

56. The number of requests from foreign governments to verify whether a Canadian organization is registered in the CSP increased from fiscal year 2011 to 2012 when there were 51 requests, to fiscal year 2015 to 2016 when there were 94 requests. In fiscal year 2016 to 2017 however, there were only 19 such requests.

Outcome 3

To what extent does Canadian industry compete internationally? To what extent is foreign investment encouraged?

Conclusion

57. Canada conducts a significant amount of international contracting. CSP efforts have opened up new markets to Canadian businesses, and enabled foreign investment in Canada.

Findings

58. There was over $11 billion of international contracting (Canada making purchases abroad) on military expenditures between April 2011 and March 2017. Nearly 65% of this was spent on military expenditures from the United States.

59. As well, the negotiations conducted by the program (required before the signing of international bilateral security instruments) enabled Canadian suppliers to access a cumulative $113.5 billion of international markets for contracts with security requirements. The bilateral agreements signed are reciprocal and enable foreign governments to hire Canadian businesses for work on sensitive contracts.

Outcome 4

To what extent are government departments' security requirements met? To what extent can departments hire contractors for sensitive work in a timely manner?

Conclusion

60. Overall, departmental security requirements are met. In general, stakeholders felt that the CSP provided key services and are satisfied with the security clauses provided by the CSP. The Personnel Security Screening Division saw higher volumes and experienced difficulties in meeting its service standards related to classified personnel screenings over the evaluation period despite an increased budget and 39 additional full-time equivalents. This suggests that departments may not always hire contractors in a timely manner. Clients noted that improvements could be made to the timeliness of screening personnel.

Findings

61. Overall, documents provided by the program indicate that companies comply with program requirements. During the scope of the evaluation 453 investigations regarding non-compliance with security requirements were undertaken. Of those, only 1 organization has had their security clearance revoked as a result of an investigation. More specifically, the contractor had assigned work to a subcontractor who was not registered in the CSP. The majority of investigations are found to be administrative non-compliance issues such as advertising their organization's clearance on their website or not following the standard subcontracting processes. Detailed numbers on the number of inspections and investigations can be found in question 9.

62. Client departments noted that security clausesFootnote 3 written by the program meet the needs of clients, but that they should be tailored to the specific department, especially in instances where the contract supports the security needs of several government departments (for example, the purchase of computer software for a group of government departments).

63. Clients also noted that 1 value-add is the consistency that comes from having a single organization conducting the security screenings. Physical document safeguarding, however, is becoming less relevant with efforts to reduce storage of paper files and clients indicated that more focus should be brought to information technology security in contracting.

64. Comparing the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year and the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, the program improved its performance against the service standard of processing a simple reliability status applications adjudicated within 7 days (from 86% to 89%). The processing time of all classified personnel screenings in under 75 days decreased from the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, from 82% to 54%. Difficulties in meeting this standard are due in part to increased requests for classified security screening in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. The Personnel Security Screening Division budget increased by nearly $2 million over that time period, and the number of full-time equivalents increased from 48 to 87.

65. Stakeholders surveyed and interviewed were generally dissatisfied with the timeliness of CSP services. Government stakeholders noted that screening personnel themselves can be faster than applying for clearance through the CSP and that this could unjustly favor the hiring of contractors already screened over those who have not yet received their clearance.

Outcome 5

To what extent does Canadian industry understand and comply with security requirements for sensitive Canadian and foreign government contracts and subcontracts?

Conclusion

66. The program made efforts to increase industry's understanding of their responsibilities in the Industrial Security Manual over the last 5 years. With a few exceptions, company security officers were generally aware of their obligations under the CSP and the Industrial Security Manual. Evidence related to industry compliance is reported in question 9.

Findings

67. The percentage of company security officer training sessions per organization decreased over the evaluation period, but over 5,300 people attended information sessions, indicating that the program is making efforts to increase industry understanding of their responsibilities in the Industrial Security Manual.

68. The program delivered several training sessions over the evaluation period to help improve company security officers' knowledge of their roles and responsibilities. From April 2013 to January 2017, 44 onsite training sessions were provided to company security officers. The percentage of company security officers in all CSP registered companies who attended the training session increased from 8% in the 2013 to 2014 fiscal year (the first year that these sessions were delivered) to 36% in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. Industry was generally very satisfied with the in-person training sessions delivered between the fiscal years 2013 to 2014 and 2016 to 2017.

69. The survey of company security officers served to ascertain knowledge of their obligations under the CSP and the Industrial Security Manual. Industry representatives demonstrated fair knowledge of their obligations. They were less familiar with their obligations in relation to the reporting of security breaches, subcontracting and the storage of classified information.

Outcome 6

To what extent are the Government of Canada's classified and protected information and assets safeguarded?

Conclusion

70. Overall, stakeholders were in agreement that the process used by the program to ensure that information and assets are safeguarded is effective, but noted areas for potential improvement. The number of investigations conducted increased slightly over the evaluation period and the results of investigations were used to improve outreach efforts and communications.

Findings

71. Inspections are conducted for every new registration in the CSP. A proportion of those will be renewed (and require a renewal inspection) and a proportion will require a follow-up inspection to ensure that they are compliant if an issue was found. The number of inspections in organizations increased from 1,624 in fiscal year 2011 to 2012 to 8,682 in fiscal year 2016 to 2017.

72. The CSP tracks the number and types of investigations performed and details on the outcomes. The number of investigations completed increased over the evaluation period from 22 in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 114 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. The percentage of investigations in active screened organizations also increased from fiscal years 2011 to 2012 to 2016 to 2017, from 0.19% to 0.55%. This represents a very small proportion of investigations overall relative to the number of active screened organizations.

73. Stakeholders interviewed were in agreement that the process used by the program to ensure that information and assets are safeguarded is effective, but noted areas for improvement. These included improvements related to timeliness of clearances and following up with companies to ensure that security requirements continue to be met throughout the contract lifecycle. Vetting organizations and foreign ownership issues is an area of risk where the program could focus more attention. More specifically, additional analysis could be done to screen the companies to ensure their overall reliability. This is also true in instances where a company may be suspended under the Controlled Goods Program due to issues with company ownership and control, but would be cleared under the CSP as more robust reviews of companies' reliability is typically not done during the company clearance process.

Intermediate outcome achievement

Outcome 1

To what extent has access to foreign and domestic government contracts and subcontracts facilitated economic opportunities for Canadian industry?

Conclusion

74. Based on an increase in the number of completed clearances, more Canadians are able to work in industries requiring access to sensitive government contracts and subcontracts. The program's service delivery had little impact on hiring or staffing decisions in private sector organizations. Businesses believe the CSP supports work abroad on sensitive contracts, but that the CSP's timeliness puts contracts at risk.

Findings

75. The largest overall industry applying for clearance in the CSP is the defence industry. Statistics Canada does not provide a breakdown of employment trends for military versus non-military employment. The number of individuals holding security clearances increased from 604,304 to 695,531 between September 2014 and March 2017. Approximately 3.4% of the Canadian labour force in 2016 was registered in the CSP and eligible to work on government contracts with security requirements.

76. Industry representatives interviewed noted that being registered in the program helped to limit the playing field and allow a smaller number of companies to compete for sensitive contracts. One also noted that especially in high-tech, it is important to be able to share information across borders in order to help fuel innovation. Timeliness with the issuance of clearances was noted as an issue by industry stakeholders however, and some noted instances where they needed to reassesses their processes in order to account for the length of time it takes to complete a CSP clearance.

77. Generally, industry representatives interviewed and surveyed indicated that the delivery of the program's services did not impact staffing decisions in their organization. Similarly, key senior officials in companies surveyed also responded that the program delivery had little impact on decisions related to hiring or staffing in their organizations.

Outcome 2

To what extent are foreign governments' sensitive information and assets safeguarded within the context of contracts with Canadian organizations?

Conclusion

78. Industry and other government department stakeholders consulted were unable to comment on the process for safeguarding foreign governments' information and assets. The program conducted a limited number of international investigations. There were 5 security breaches over the evaluation period, and all were deemed low risk by the program.

Findings

79. There were 5 known security breaches reported since 2011. Severity and nature of the breaches were considered low risk (for example, packaging was damaged during transit and contents were visible). There were 3 international investigations over the evaluation period. In only 1 instance actions were taken to remedy the situation; an advisory letter being sent to the company security officer of the company informing them of the breach and follow-up actions. The results of the 2 other investigations did not indicate a need for corrective measures.

80. Industry representatives interviewed could not comment on the program's process for safeguarding foreign government information and assets as their companies had not conducted business internationally.

81. Program management noted that the safeguarding processes are as stringent for foreign information as are for domestic. In addition, international contracts require a foreign ownership, control or influence evaluation (evaluation is an administrative determination of the nature and extent of foreign dominance over the contractor's management and/or operations), which provides foreign contracts (Government of Canada purchasing from a foreign company) an extra level of scrutiny which is not mandatory for most domestic contracts.

Outcome 3

To what extent does Canada uphold its North Atlantic Treaty Organization industrial security obligations and maintain the trust of its allies?

Conclusion

82. Results of North Atlantic Treaty Organization compliance audits show that Canadian companies are meeting their international security obligations and maintaining the trust of its allies. There were no reported breaches of North Atlantic Treaty Organization policy in the last 6 years.

Findings

83. North Atlantic Treaty Organization compliance audits are conducted every 2 years at Global Affairs Canada, Department of National Defence and PSPC. The consolidated results are classified, but the last 2 audits deemed the Canadian contract security performance rating to be satisfactory (2013 and 2015), which is an improvement over the 2011 rating, partially satisfactory.

84. There were no reported breaches of North Atlantic Treaty Organization policy during the evaluation period.

Conclusion: Performance

85. Overall the program is meeting the security requirements for domestic and foreign government contracts, and government information is safeguarded. Clients are generally satisfied with program services, but several were dissatisfied with the timeliness of classified security clearances. Contractors working for the federal government generally understand their roles and responsibilities related to security in contracting. The Canadian government undertakes a high number of contracts with security requirements annually, with very few instances of information breaches. The program enables secure international contracting, and provides services to foreign governments to help ensure that their information will be safeguarded while in the custody of Canadian contractors.

Efficiency and economy

86. Demonstration of efficiency and economy is defined as an assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and outcomes. Efficiency refers to the extent to which resources are used such that a greater level of output is produced with the same level of input or, a lower level of input is used to produce the same level of output. Economy refers to minimizing the use of resources. A has high demonstrable economy and efficiency when resources maximize outputs at least cost and when there is a high correlation between minimum resources and outcomes achieved.

87. Total financial figures were generally used in this section. Of the program components, only the financial and output information for personnel screening was sufficient to conduct a simple analysis, thereby limiting the examination of efficiency and economy of the CSP.Footnote 4 Limited information on program economy was available as a result of outcome attainment being influenced by a large number of factors outside of the programs scope. A number of initiatives are planned to further improve program delivery and client services.

To what extent did the program undertake activities, deliver services and products, and operate in an efficient manner? To what extent did the program achieve similar results with fewer resources? To what extent did the program undertake activities, deliver services and products, and operate in an economical manner?

Conclusion

88. Expenditures remained stable over the evaluation period, with a reduction in operations and maintenance costs to cover higher salary costs. While there was an increased number of full-time equivalents, the volume of incoming requests for screening also increased, adding time and cost to the processing. In 2016, the program obtained Treasury Board approval to increase revenues through cost-recovery by 25% over the 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019 fiscal years to address the increase in security screening requests. Several of the CSP's processes have been streamlined, although resulting efficiencies could not be quantified.

Findings

Economy

89. Actual program expenditures were relatively stable over the 6 year evaluation period at around $24 million annually. The cost-recovery revenue generated by the program annually accounted for $16.88 million in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year and $17 million in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, and the program saw an increase in net A-base program budget (budget less cost-recovery revenue) from $7.1 million in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to $6.3 million in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year.

90. The number of full-time equivalents increased from 187 in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to 252 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, representing an increase of 65 full-time equivalents. The overall expenditures remained in line with those of previous years as operations and maintenance funds were converted into salary dollars.

91. Comparing the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year and the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, the personnel screening component of the program improved its performance against the service standard of processing a simple reliability status application within 7 days (from 86% to 89%). The processing time of all classified personnel screenings in under 75 days decreased from fiscal years 2011 to 2012 and 2016 to 2017, from 82% to 54%. Difficulties in meeting this standard are due in part to increased requests for classified security screening in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. In 2016, the program obtained Treasury Board approval to increase revenues through cost-recovery by 25% over the 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019 fiscal years to address the increase in security screening requests.

92. With respect to the personnel security screening component of the program, the salary budget increased by nearly $2 million over the evaluation period, and the number of full-time equivalents increased from 48 to 87. There was also an increase in the average cost to render a decision on personnel security clearances requests (either reliability status or security clearance) from $34 in the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year to $41 in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year.

Efficiency

93. Program management indicated that the program undertook several efficiency reviews over the years, and through those exercises streamlined and re-engineered different processes, such as reducing the process steps to issue international security clauses. The visit request process was streamlined and common forms for the members of the Multinational Industrial Security Working Group were created. Similarly, a Lean Six Sigma business process mapping exercise took place in 2015, with recommendations to further improve business procedures, processes and risk tolerance. Changes were made to improve processes in the personnel screening and investigations divisions, while other recommendations were deferred until a new information management system could be implemented. Some operational efficiencies were gained by lowering paper consumption and storage costs by moving towards conducting more of their business electronically such as the introduction of electronic signatures in April 2017. Program management indicated that key to moving the program forward is the new case management system which will allow them to manage files according to risk.

94. A treat and risk assessment is planned for 2018 to further examine program risks and map mitigation strategies. As well, the modernization of the CSP's aging technological platforms in the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year is expected to further improve the efficiency of the screening process and reduce the administrative burden for suppliers.

Conclusion: Efficiency and economy

95. The program experienced challenges in the delivery of timely and cost-effective personnel screenings. A number of initiatives are underway to further improve program delivery and client services. Limited information on program economy was available as a result of outcome attainment being influenced by a large number of factors outside of the programs scope.

Management response

96. The Departmental Oversight Branch Contract Security Program is a key contributor to the national security framework, engaging closely with Security and Intelligence agencies and departments to identify, evaluate and mitigate security risk in government contracting. This includes the application of safeguards to all phases of the government contracting process as a lead security agency, allowing Canadian industry to participate in domestic and international government contracting while safeguarding sensitive government information and assets.

97. Since the completion of data gathering for this evaluation in March 2017, the CSP has seen significant, sustained performance improvement. Publicly reported service delivery standards for all screening levels have been met or exceeded over the past 4 quarters. In addition, processing timelines for security requirement check lists have improved such that the 15-day standard is met 80% to 90% of the time. These performance improvements have resulted from: transition to paperless processes, on-going workforce stabilization, re-engineering of security screening processes, and increased use of risk-based prioritization for complex files and investigations. In addition, pilot programs to address domestic visit requests (with the Department of National Defence) and regional security investigations are underway and are expected to further decrease processing times.

98. Given that the steps taken over the last year have led to sustained performance improvement, Departmental Oversight Branch does not consider the development of a risk framework to be necessary in order to balance security and client service, with a view to improving process times. However, an ongoing threat and risk assessment will be used to apply a risk-based lens to the CSP, with a view to improved risk mitigation in an evolving threat environment. In addition, recent public opinion research conducted on the CSP has provided baseline data that will be used to evaluate progress related to improving industry's awareness of its security obligations in the government contracting process.

Recommendations and management action plan

Recommendation 1

The Assistant Deputy Minister, Departmental Oversight Branch should develop a risk framework to balance the 2 core objectives of security and client service with a view to improve processing times for classified personnel screening, visit requests and security requirements check lists. Furthermore, this framework should include an approach to Foreign Ownership, Control or Influence to mitigate the risk of unauthorized access to sensitive information as well as information technology security considerations in contracting.

Management action plan 1.1

In order to improve processing times for classified personnel screening, visit requests and security requirements check lists, the following has been undertaken:

- transition to paperless processes using e-signature

- implementation of telephone interviews for minor adverse and instances of non-disclosure

- ee-engineering of internal security screening process resulting in significant improvements in processing times

- development and implementation of new risk-based matrixes for complex files to reduce the number of files requiring security screening interviews and investigations

- stabilized resources: reduced dependency on contingent workforce

- development and implementation of a pilot (through March 2020) to develop a regional security screening investigator capacity to improve performance in key regions

- development of a plan to pilot the processing of domestic visit requests by the Department of National Defence. Pilot to be launched by quarter 1 of the 2019 to 2020 fiscal year

Management action plan 1.2

As part of a more holistic assessment of the factors and risks that company ownership may represent to the security of information, the CSP will undertake a review of ownership processes, informed by the ongoing threat and risk assessment, and develop recommendations regarding risk-based review of ownership as part of the registration process.

Management action plan 1.3

PSPC will adopt a risk-based approach to addressing IT inspection requirements to allow for the implementation of an offsite inspection process for low risk files to increase efficiency.

Recommendation 2

The Assistant Deputy Minister Departmental Oversight Branch should strengthen the program's performance measures related to its security objectives. This could include measures to ensure that company security officers are better aware of their role in reporting security breaches and events, and of the security measures required for subcontractors.

Management action plan 2.1

The Contract Security Program will take the following steps to strengthen program performance measures related to its security objectives, as they relate to industry awareness of contract security obligations:

- review and update communications material for industry regarding their contract security obligations related to breaches and subcontractors

- launch a new online training course for company security officers to raise awareness of the roles and responsibilities of contractors in complying with contract security requirements, including those related to breaches and subcontractors

- explore the feasibility of making online training mandatory, including a phased-in approach (for example, 1) pilot project; 2) mandatory in non-compliance cases; 3) mandatory for all)

- re-write the CSP's Industrial Security Manual to focus only on program requirements, and make it more user-friendly for to industry

- review, assess and make recommendations on how to simplify clearances of subcontractors in the CSP

Appendix A: description of program activities

Below is a summary of the activities performed by the CSP.

Company registration

Review company security clearance requests: Companies must be registered with CSP to access protected or classified information within the scope of a contract. A government-approved sponsor such as a procurement officer submits requests to CSP requesting a company be screened.

Analyse company information: Upon receipt of a valid request for company screening, the CSP contacts the organization and requests information on areas such as the company's structure, ownership and legal status, and a signed agreement/attestation from the company security officer.

Identify company security officer and key senior official clearances required: As part of the screening process, companies must appoint a company security officer and identify key senior officials in order to be granted organizational security clearances under CSP. The company security officer is responsible for: ensuring that staff receive the required screening and security briefings; that breaches are reported; and that physical security requirements are met.

Review files for compliance: The program reviews documentation at both the beginning and end of the contracting process to ensure that proper security clauses are included in contracts, that these requirements are being met by the selected suppliers once contracts are awarded, and that organizations are in compliance with active contract security requirements, CSP requirements and the provisions of the Industrial Security Manual.

Grant, deny and revoke facility security clearances and designated organization screenings: If the organization does not comply with CSP and contract requirements, their organization security screening may be denied or terminated. Compliance is evaluated during inspections and investigations.

Personnel screening of company employees

Apply tests of reliability and loyalty: Once a personnel screening application is submitted, the CSP performs/obtains a reliability test involving a law enforcement inquiry (verified by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) and may perform a financial enquiry. A loyalty test may also be performed, which involves a security assessment from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

Conduct resolution of doubt interviews: When a security concern is raised during the screening process, CSP undertakes subject interviews to obtain additional information from the applicant to assess eligibility or to assess the circumstances or actions that raised the concern.

Grant, deny and revoke reliability status and/or security clearances: Before granting or denying a clearance, CSP: ensures the applicant is eligible for screening; requests information from the company security officer; analyzes personnel files, conducts and assesses checks from security partners (the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Canadian Security Intelligence Service), and conducts interviews and processes fingerprints as required.

Input termination requests: Organizations submit personnel security screening termination request forms for their employees directly to the program, as necessary. Upon receipt, CSP terminates the clearance in its industrial security system.

Inspections and investigations

Inspect document safeguarding capabilities and/or information technology systems: The CSP inspects facilities and information technology systems as necessary to confirm document safeguarding capabilities, and to investigate incidents and security breaches. Periodic inspections are conducted to ensure adequate safeguards.

Investigate incidents and security breaches: The CSP conducts administrative investigations when information or assets have been compromised (lost or disclosed, modified or destroyed without authorization). Company security officers are required to report such incidences to the CSP.

Monitoring and reporting: An organization's status and compliance with CSP requirements are monitored and reported. Changes to an organization's status with the program are reported to concerned parties, such as the sponsor who submitted the organization's screening request.

Contracts

Review and advise on pre-contractual documents: the CSP reviews pre-contractual documents and provides contract clauses describing security requirements to government departments.

Review security requirements check lists and identify appropriate contract security clauses: All contracts, standing offers or supply arrangements and subcontracts with industrial security requirements must include a completed security requirements check list. At the contracting stage, the CSP reviews the security requirements check list provided by client departments and identifies appropriate security clauses for inclusion in contracts.

Process visit clearance requests: The CSP approves visits to secure Government of Canada sites or Canadian industrial sites where work on protected or classified information or assets is taking place. The program also works with its counterparts in other countries to approve visits abroad.

Process document transmittal requests: The CSP will monitor and support the international or domestic transfer, through government-to-government channels, of classified and protected information and assets between Canadian and foreign governments and industry.

Conduct foreign ownership control and influence assessments: The CSP conducts these evaluations to determine whether a foreign third-party possesses or could possess dominance or authority over a company allowing unauthorized access to classified information.

Information, awareness and training